PEOPLE

ORM celebrates 10 Years – To Hell and Back – Matina Jewell

WORDS: PHOTOGRAPHY

The 1000-pound bomb, fired from an Israeli fighter jet, whizzes past Captain Matina Jewell so close she can almost reach out and touch it. Then comes the massive blast as the bomb explodes into the Hezbollah militia base just 75 metres away. Shrapnel, including huge lumps of concrete laced with star pickets, rains down on Capt Jewell and her fellow soldiers. They survive that strike, but within days all her colleagues will be dead. And she will be lying in hospital with a badly broken back, her burgeoning military career in tatters.

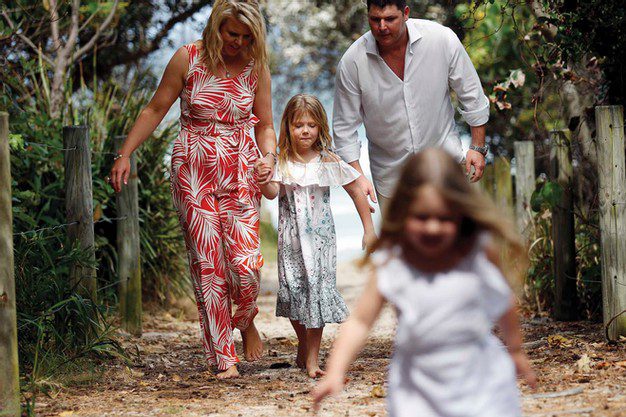

It’s a long way from the bloody battlefields of the Middle East to the idyllic Tweed Coast, literally and figuratively, but it’s where Ocean Road finds retired Major Matina ‘Matti’ Jewell today. She buzzes us in to her stylish home, kids’ toys at the door and a swing set in the manicured yard. Matti, a petite, attractive blonde with a welcoming smile, is padding around barefoot.

Clent, her classic tall, dark, and handsome husband, a marketing executive, is working from home and also greets us with an easygoing grin and an amiable chat. Justifiably proud of his wife’s inspiring achievements in military and civilian life, he fires up his laptop and plays an emotional video snapshot of the horrific warzone experience 12 years ago that changed both their lives irrevocably.

Matti was born and raised at Alstonville in the picturesque Northern Rivers hinterland. She attended Alstonville High, where her father, Roger, was a teacher. Her grandfather, who served in Papua New Guinea in WWII, was the only member of her family with military connections.

“So it was quite a surprise to my parents when I announced I was going to try and qualify to become a cadet at the Australian Defence Force Academy,” Matti tells us over freshly brewed coffee in her living room.

The ‘sliding doors moment’ came, she says, after she represented Australia at volleyball — one of a plethora of sports at which she excelled — in China at the age of 16.

“Coming from this beautiful part of the world, to travel to Shanghai and Beijing all those years ago and seeing all the pollution and poverty… I’d never seen that level of in-your-face-type poverty that I experienced on the ground in those two cities,” she says. “I guess I came back a far more appreciative teenager of what we have in Australia. I understood that I’d taken my upbringing for granted up until that point.”

The China trip helped shape Matti’s thinking when it came to choosing her career path.

“I knew that I wanted to go and have that humanitarian aid aspect to help disadvantaged communities that were in need and in crisis,” she says.

“I wanted to work in a team environment as most of my sports were team events rather than individual sports. I loved being captain of those sporting teams, so I wanted a leadership role in my career, and I also wanted to do my university studies.

“I’d also seen my parents struggle financially to put my older brother Mark through an architecture degree, so part of me really wanted to try and get some form of scholarship where, at 17, I could be financially independent. The ADFA really ticked all of those boxes for me.”

She duly landed a scholarship and headed off to Canberra for three years of study at ADFA, where she gained a science degree, and another year of officer training at the Royal Military College at Duntroon.

Upon graduating as a Lieutenant in 1997, her first deployment was to Perth, where she trained with the elite Special Air Service Regiment (SAS), learning Indonesian, and also worked in the Joint Logistics Unit servicing the Australian Army and Royal Australian Navy in Western Australia. After three years in Perth, she was promoted to Captain and made second-in-command of the army detachment onboard the HMAS Kanimbla, then the largest warship in the Australian navy fleet. Two weeks after boarding Kanimbla, she was hurled headlong into the deep end.

“I’d only just been promoted to Captain, but the army Major onboard fell ill and had to leave the ship,” Matti says.

“So I was promoted for the second time in two weeks, to acting Major, to actually command the army department on Kanimbla for next two years. I had 20 soldiers under my command and an embarked force of up to 450.”

Her first mission, in July 2001, was to the troubled Solomon Islands as part of an international peacekeeping force. Then the 11 September terrorist attacks rocked the world, and the United States invaded Afghanistan, she was sent to the North Arabian Gulf to perform patrol duties with the US Navy Seals.

“We were working with the Navy Seals boarding smuggler ships that were coming out of Iraq and Kuwait, smuggling arms and weapons and so forth, as well as alongside the Kuwaiti special forces in support of [Allied] operations in Afghanistan,” Matti explains.

“I was responsible for the planning, coordination, and execution of amphibious offloads for not only Kanimbla but multiple navy ships. That involved movements of up to 1000 soldiers, their vehicles, and all their equipment off these ships to get them to a beach. And potentially I’d be putting them into enemy terrain.

“To run those operations, I’d have at my disposal up to six helicopters and 10 watercraft. At 23, it was quite a big responsibility on my shoulders.”

Matti was also the diving officer onboard Kanimbla, having become the first woman in the Australian Army to qualify as a navy diver (as well as in fast-roping from helicopters).

“The navy diver’s course was very intense physical training, the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” she remembers. “The course was held in winter and you’re not permitted to wear wetsuits until you qualify as a diver, so you’re in overalls in cold water. It was freezing, physically demanding, and you have to deal with challenges such as sleep deprivation and so on. It’s a really tough course.”

Following a six-month stint in the Gulf, HMAS Kanimbla was deployed on another back-to-back operation, this time to Christmas Island as part of Australia’s border protection efforts. Matina was then sent back to the Solomons, where Matti helped track down brutal warlord Jimmy Rasta, who had cut a bloody swathe of terror through the Pacific nation as the leader of the Malaitan Eagle Force militia. Embedded with a Papua New Guinea infantry patrol, she was sent to Rasta’s home island of Malu’u in the Solomons to try and locate the elusive rebel.

Matti and her patrol chanced upon him in a local produce market where, even more bizarrely, he invited them to a dinner he was hosting.

“I wouldn’t say he was friendly — this guy’s been accused of horrific atrocities, going through villages with homemade weapons and just killing entire villages,” she says. “He wasn’t the kind of guy to drop your guard with. He asked one of the PNG soldiers who the boss man was. It was much to my dismay when the soldier pointed to me and said, ‘This is our leader’.

“Rasta had this sheer arrogance that he was untouchable in the Solomons. He knew that there was a Coalition force out there looking for him, but he thought that he was too much of a power in that region for anything to happen to him and his men.”

Matti knew she needed some sort of evidence that the man they had met at the market and invited them to dinner was indeed Jimmy Rasta, who had gone to ground for so many months and had now suddenly materialised.

“So I’ve got these crazy selfies with a warlord that I’ve sent back to headquarters back in Honiara, telling them that ‘we’ve located Jimmy Rasta and he’s asked us to a party tomorrow night’,” Matti chuckles.

“It was one of the crazy moments of my career. As a result of my attending that function with Jimmy Rasta and the Malaitan Eagles, federal police were able to track Rasta and his men, and a number of weeks later he was arrested and charged with a number of crimes under Solomon Islands’ civil legal system.”

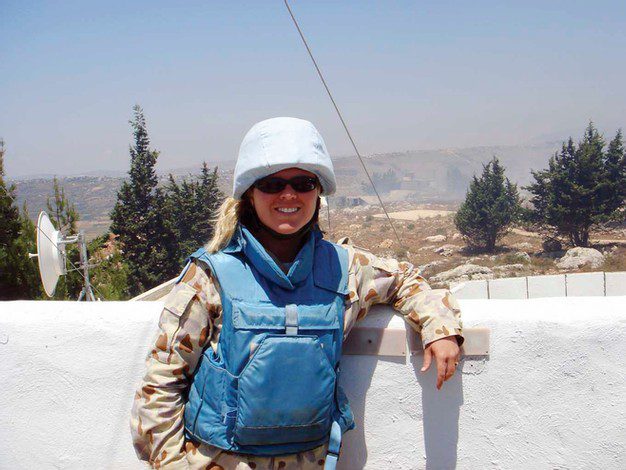

In August 2004, aged just 28, Matti was selected by the Australian Army for a prestigious 13-month role as a United Nations Military Observer, or peacekeeper, in the ever-volatile Middle East. She would be the only Australian, and the only woman, at the UN patrol bases in Syria and Lebanon. But first she had to undergo a gruelling crash course in Arabic at the Australian Defence Force language school at the RAAF Base at Laverton, south of Melbourne, as well as a combat medic course.

Being selected for the historic United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO) mission was a huge honour, but there were a couple of not-so-small complications. One, she’d met Clent at a military mate’s wedding in the NSW Snowy Mountains, and they’d fallen in love. And two, she was suffering from an undiagnosed medical condition that had seen her rushed to hospital with severe abdominal pain and vomiting. However, she passed the medical tests and in early 2005 bid Clent a tearful farewell at Sydney Airport.

The first seven months of her posting were spent in Syria, manning two observation posts overlooking the UN-enforced ‘area of separation’ with Israel and conducting seven-day patrols of the Golan Heights. She lived among the locals in a rented apartment in Damascus and worked in the OPs alongside fellow peacekeepers from more than 20 nations.

“At each of my patrol bases in Syria and Lebanon, I was the only Australian and also the only woman in those entire patrol regions,” she says.

“It was a fantastic opportunity to work with these different nationalities while serving in this fascinating part of the world. Damascus was an amazing city, so rich in history and culture. I also got to explore other beautiful cities such as Aleppo.

“Tragically, as a result of the civil war that’s still going in Syria, much of that incredible history has all been destroyed. It’s quite sad that we’ve lost all that history and we’ve lost so many people in that conflict. So many people have been made refugees as a result of the war that is continuing.

“I think for most Australians it’s really hard for us to comprehend the idea of war breaking out this afternoon, bombs coming down and you’ve virtually only got time to grab your children and run with what you have. And most of these people in Syria are really highly educated, successful people, and they’re leaving behind their entire lives.”

After seven months in Syria, Matti was sent to Lebanon where 48 hours after arriving, she had to fight off two attackers who accosted her on motorbikes as she walked to a meeting with a UNTSO superior in the coastal town of Tyre. They tried to pin her down, but she kicked one in the groin with her steel-capped army boot and fought off the other.

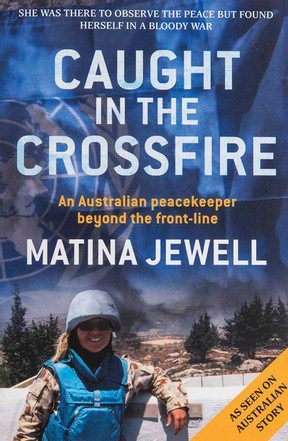

“I am a Captain in the Australian Army!” she yelled at them in Arabic, she recalls in her best-selling memoir, Caught in the Crossfire. “I am in Lebanon working for the United Nations.”

The men fled but Matti was left badly shaken. However, it was not enough to deter the tough little Aussie digger, and a few days later she started her first seven-day patrol on Patrol Base Khiam: a tennis court-sized post surrounded by razor wire, perched on a ride line 130km south of Beirut. Overlooking the UN ‘Blue Line’ between Lebanon and Israel, the base was surrounded by three Hezbollah posts, including one just 75 metres away.

Manning the patrol base with her were four fellow peacekeepers who would become like brothers to her — Major Du Zhaoyu (China), Major Paeta ‘Wolf’ Hess-von Kruedener (Canada), Lieutenant Jarno ‘Big Mack’ Makinen (Finland), and Major Hans-Peter Lang (Austria).

On 12 July 2006, 24 hours before her tour of duty was to end, the 34-day Lebanon War erupted.

“Hezbollah had gone down to the Israeli border and ambushed an Israeli Humvee patrol,” Matti explains. “During that attack, they killed three Israeli soldiers and captured two more, and that is what sparked the entire 2006 Lebanon War.

“We went in a split second from monitoring a peace agreement to being on the receiving end of full-scale warfare — fighter jets, attack helicopters, Merkava tanks, artillery fire. All of that was coming from Israel into our region, surrounding our base. Hezbollah were also firing Katyusha rockets into Israel.

“For my team at Patrol Base Khiam alone, we’d go on to survive more than 50 near-misses during that war.”

Rockets and bombs rained down on Hezbollah positions around PB Khiam before an eerie silence descended. Then, suddenly, at Matti’s eye level and a mere 30 metres away, a 1000-pound laser-guided aerial bomb, fired from an Israeli fighter jet, was heading toward her and her UN comrades. It was as big as a bathtub and was so close she could see the stabilising fins at the rear of the projectile. There was an almighty explosion as the bomb slammed into the Hezbollah base just 75 metres away.

“I was actually on the rooftop at Khiam when that bomb impacted,” she says. “It happened in a split second, but it just felt like slow-motion around me. Like I could put my hand up and touch this massive bomb as it went into the base. I just had enough time to tell the guys to get down as it exploded.

“Huge amounts of shrapnel came in; a fireball ripped over our heads. The shrapnel was like huge chunks of concrete with twisted star pickets through the centre right through to fine pieces of metal shrapnel. We were all covered in smoke and ash.”

The peacekeepers reported the near miss and took shelter in the bunker, but then had to return to the rooftop to document the violation of the peace agreement.

“The UN classified a near miss from those types of bombs as having impacted 1km away, and this one was just 75 metres,” Matti says. “It was a sheer miracle we didn’t take casualties in the first hour of the war at Khiam.”

On the second night of the war, Matti and her comrades were again forced to take cover as artillery shells exploded into the base itself.

“One 155mm high explosive round exploded about 20 metres away from us as we ran to the bunker,” she says. “The only reason I’m still here to tell the tale is because the firing mechanism malfunctioned.”

After seven days of hellfire, Matti finally made it out of PB Khiam, replaced by Hans-Peter as part of a rotation. She had been looking forward to a Red Sea dive holiday with Clent but those plans were all gone now as a result of the war. First she had to make it back to UN headquarters in Tyre, alive.

“I was tasked to command a convoy of UN armoured vehicles — I had two armoured personnel carriers and 16 Indian and Ghanaian infantry soldiers under my command,” she recalls.

“That drive from Khiam to Tyre would normally take about two hours, but all the roads from Khiam to Tyre unfortunately ran parallel to the border, and of course that’s where all the fighting was happening. So it actually took me two days and near-misses from both sides to get that convoy through.”

Using her Arabic language skills, Matti was able to get directions from a Lebanese police officer to cut through a banana plantation that got them to the outskirts of Tyre.

“But as we were making fast speed to Tyre, I’d been told that Israel was about to conduct the last air strike of the entire war and the road that I was on was one of the roads to be targeted,” she says.

“We were making high speed into town, and there were a lot of panicked civilian drivers around us also trying to reach shelter.

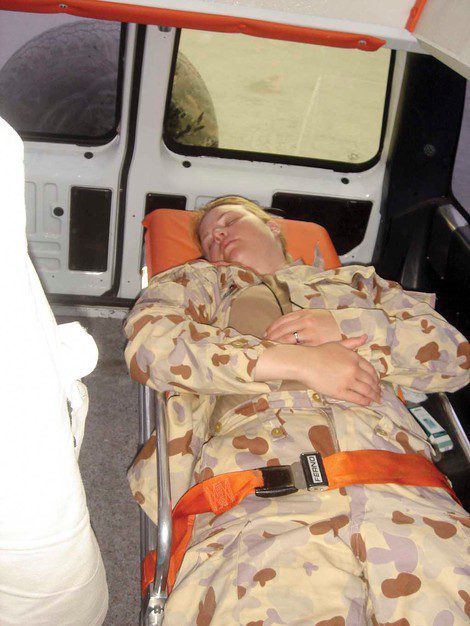

“I was on the radio to HQ and didn’t see that my driver was about to do an evasive manoeuvre. I was thrown into the bulletproof windscreen, which broke my back in five places.”

Despite suffering two crushed vertebrae, three more fractured vertebrae, a ruptured diaphragm, and multiple internal injuries, Matti managed to get the convoy back to the UN compound.

With UN medivac plans in disarray amid the chaos of the war, she spent two days lying on a tiled floor without any morphine, as Israeli bombs continued to fall.

“The UN was now scrambling trying to come up with an alternative to get me to hospital,” she says.

“That ended up being a 20-hour boat ride across the Mediterranean Sea to Cyprus, with Lebanese civilian refugees and also the families of the UN peacekeeping force.”

Fortunately, there was a doctor onboard with morphine, and Clent was at her side.

“Poor bugger, he just arrived in Lebanon to have a romantic, relaxing beach holiday with me, but he got a far more action-packed holiday in a warzone,” Matti says with a wry chuckle.

“Everything he was put through in the war and the aftermath was clearly outside his comfort zone, but he’s obviously a sucker for punishment. After all that I put him through, he even asked me to marry him. He must have thought it was going to get better [laughs].

“The day we evacuated out of Lebanon was actually his 30th birthday. I grabbed Clent’s hand and said, ‘See baby, I didn’t forget your 30th — I got you a Mediterranean cruise for free!’”

It was in hospital in Cyprus that Matti learnt her four closest colleagues — Wolf, Big Mack, Du, and Hans-Peter — had been killed in a direct hit on PB Khiam by another 1000-pound Israeli bomb. The memory still brings tears to her eyes.

“They were like brothers to me,” she says quietly. “Each of them were great men and great characters, and all of them had families.

“Those types of work environments that have such high risk often create very strong bonds. I spent over a year with these guys working in an environment where every day we went out on patrol, or even just being at the base, we were literally putting our lives in each other’s hands.”

‘Survivor guilt’ was one of the many issues Matti faced when she finally returned to Australia.

“All of my team had children,” she says. “I was still single with no dependents. That survivor guilt played so heavily on me I actually got to the stage where I resented I was still alive. I was wishing I could have replaced even just one of the guys, so it wasn’t one set of kids that was having to grow up without their dad.”

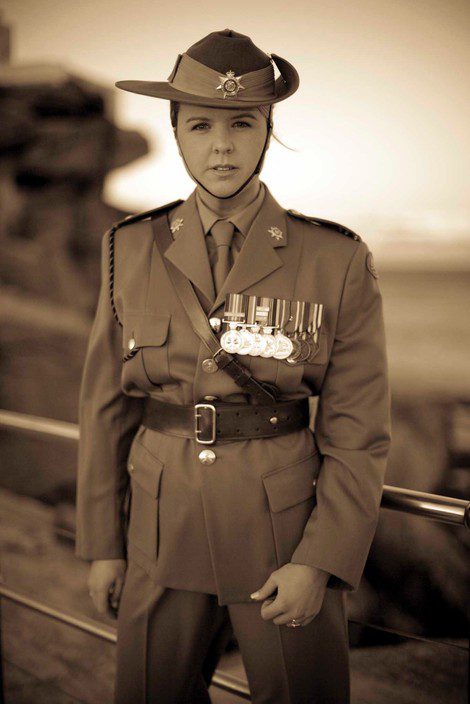

The survivor guilt and post-traumatic stress disorder, coupled with her severe physical injuries, eventually led to Matti being medically retired from the army. Having endured all that, she then suffered the ignominy of having to fight the federal government to recognise her war service — which saw her awarded two Republic of Lebanon war medals — and fight for Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) health cover so that her ongoing medical treatment would be covered.

“It was just another layer of problems and challenges that I probably didn’t need at that stage,” she says.

“I’d lost my teammates in Lebanon, I’d lost my career through injury, I had the survivor guilt, and PTSD, the flashbacks to the war, depression. I was struggling to get out of bed; I was in a spinal brace for a year.

“Then to layer on top of that battles with the government … there was that feeling of being let down by the people who had sent me to do this mission.”

After then-prime minister Kevin Rudd finally approved her UN mission as ‘warlike service’, and gaining access to DVA health benifits, Matti vowed to ensure no more diggers would have to go through the same turmoil.

“I guess I became very passionate and driven to ensure that we learnt from those experiences and change those processes to protect our injured veterans into the future,” she says. “I feel really privileged to have served on the Prime Ministerial Advisory Council to give back my experience and effect positive change and champion change for wounded veterans.”

Matti has also served on the National Mental Health Commission board and is an advisor to the Suicide Prevention Commission in a bid to help heal the emotional wounds of military service.

“I’m just kind of sharing my experiences and trying to help fix some of our processes so we can better support our defence personnel, particularly our veterans,” she says. “Because at the moment we’re actually losing more veterans at home through suicide than what we are on the battlefield.”

Matti and Clent married in 2008.

“We’d been to hell and back by that stage,” Matti says.

Then she adds with a chuckle: “I thought we’d been tested and be able to survive anything, but then we had two small children — two cute girls [Sierra, 6, and Kyah, 3] that makes commanding 500 soldiers in a war zone look like a walk in the park!”

Matti says in many ways becoming pregnant with Sierra helped her to deal with the survivor guilt.

“It helped give me a reason that this is maybe why I’ve survived,” she says, “and it gave me another reason to live. All of us in life need purpose and meaning to help us succeed in life to be the best version of ourselves.

“For me, having hit rock bottom, the girls were an absolute blessing. Who knows what they’ll go on to do?”

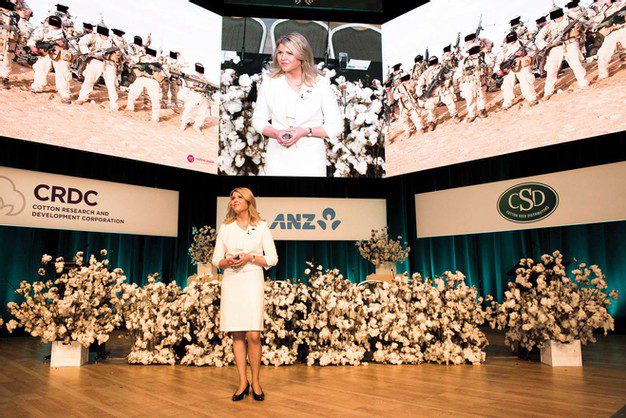

In 2010, Matti was the subject of one of the most-watched Australian Story episodes of all time. The two-part documentary has led to a thriving post-military career on the speakers’ circuit, her inspirational story of leadership in the face of adversity resonating strongly with many of Australia’s biggest corporations and industry groups.

“I get to meet people from all different walks of life and learn from them as much as they might learn from me,” she says.

“It might be a managing director for a global company and six of his directors around a boardroom table or 10,000 people in a stadium.

“It’s great to be able to share my experiences to help people improve their own lives. It’s also a privilege to honour my teammates on that platform, to share the legacy of their story and their lives.”

Matti has returned to her fallen comrades’ homelands to visit their graves and to pay her respects to their families. She plans to return to PB Khiam, now a memorial, once it is safe to do so.

Other accolades and honours have come Matti’s way, including being selected as a member of the National Commission on the Commemoration of the ANZAC Centenary, serving alongside former prime ministers Bob Hawke and Malcolm Fraser. Her duties advising the federal government on how best to commemorate 100 years of Australian military service ended recently with the centenary of the armistice of the Great War on Remembrance Day.

She was also recently named one of 100 ‘Women of Influence’ by the Australian Financial Review and Qantas.

Matti says living on the Northern Rivers, only 20 minutes from Gold Coast Airport, allows her to enjoy an ideal work–life balance with her family.

“I kind of have a rule that I don’t like to spend more than two consecutive nights away,” she says. “Both of the kids travelled with me while I was breastfeeding and did more than 100 flights the first year of their lives.

“I’m very fortunate to be able to make time and be here for my kids. And living where we do is very healing. You know that within half an hour of landing at Coolangatta, you can be at the beach with the kids, leave whatever you’re doing behind, and be really present and focused with them.”

Matti’s autobiography, Caught in the Crossfire, was published by Allen & Unwin in 2011 and continues to sell well. It was the first book in Australia to boast QR code technology, allowing readers to view videos from Matti’s year of living dangerously in the Middle East in interactive style.

Her amazing life story has also been optioned by Hollywood, and she has even held talks with Margot Robbie’s management with a view to the Gold Coast-raised A-lister playing the starring role of Major Matina Jewell.

“It’s still in script development, but I’ve been asked my preference on who I’d like to play me,” she says.

“It’s a crazy experience for a kid from the Byron Bay region to find yourself in Hollywood, being asked whether you have a preference between Charlize Theron or Margot Robbie to play you in a movie. I just joined the army when I was 17 and would never have imagined the journey that I’ve been on thus far.”